Interrupted Game(2009 revised 2016)

Secret documents, scanned in a bad quality and slapped straight on the front pages of newspapers and magazines, is a common way of informing about corruption in Croatia and Bosnia. The level of corruption in the post-totalitarian states in the Balkans is so high that it is impossible to unravel, analyze and prove one case before the next one turns up. If, as a free and independent newspaper, you can do nothing else, you can at least present crucial documents and evidence to the public directly. The public might not be able to analyze the given information, though, but the files may at least have a symbolic value in themselves. Most people still tend to regard such ‘disclosures’ as direct and uncorrupt images of truth itself.

This quite literal form of documentarism, characterising independent, post-totalitarian media such as the Croatian weekly Nacional or the Bosnian newspapers Dani and Slobodna Bosna, has a number of interesting features in common with Amel Ibrahimovic’s and Slaven Tolj’s way of working. Like the reporter, these artists are looking for the one conclusive document in the surroundings, i.e. the event, the coincidence or the newspaper photo that can condense a confused complex of information into a single comprehensible point. As Tolj said himself in a conversation with Ibrahimovic,* there is actually “no element of rendition” in his art, “but only the information that surrounds us.” This lack of rendition, however, should not be taken to imply that he does not make aesthetic works of art, but rather that he “perceives” them more than he “produces” them. Instead of transforming reality into art objects, he subjects phenomena and occurrences in his surroundings to an aesthetical gaze, and recontextualises them as art pieces. As opposed to journalism, however, Tolj and Ibrahimovic are not seeking to approach reality in some ‘pure’ form. The aim is to lay bare significant poetical, and thus emotional, truths of the world we live in – truths we cannot arrive at by way of the media that purport to describe reality for us.

Tolj and Ibrahimovic have pointed out four examples of how this kind of perceptual and recontexualizing practice unfolds. An idea can emerge just from a passing image found in a paper or in the streets, that nobody really notices or ascribes any deeper meaning to. This is indeed the case in the title work of the show in Overgaden. Tolj’s Interrupted Game (1993) which consists of two simple b/w photos of a modest tennis ball lodged in a volute on the cathedral in Dubrovnik, and children playing tennis. In order to understand the actual extent of the motive, you need to know that especially before the Yugoslav Wars children used the cathedral wall for tennis practice or to ‘play wall’ and that, following the outbreak of the war, the square became a crucial target area for snipers. This way, the innocent children’s game was not only interrupted, but also intensified by the far more brutal war games. The tennis ball, then, is a simple image of a number of complicated issues in relation to political games, territorial notions, religious conflicts, East-West tensions, loss of innocence, and obstruction. Behind this simple image, in other words, we find a wealth of other motifs. Together, they form a series of associative, emotional, and composite truths of the war that may at first seem rather obvious. On the other hand, however, they are quite difficult to elucidate by way of conventional journalism or political analysis.

The interplay between journalistic and poetic reality was even purer, perhaps, in the work Untitled, that was shown only once, in 2000. In this case the work was based directly on a newspaper photo of a very longhaired girl who had lived as a refugee for ten years, unable to return to her home town or her family. Reportedly, the girl had decided to let her hair grow until the day she was able to return. Tolj was deeply fascinated by the picture, cut it out and transposed it from a documentary photo into a work of art by blowing it up to full life-size. Since it was the growth itself that was important, it was crucial to give the hair a physical presence. The photo was arranged with a row of chairs for the audience. When sitting there looking at the girl, as if in a cinema, a peculiar kind of dynamics arose, and you got the feeling that the hair somehow continued to grow right before your eyes. Thus, even if it was a photo, it felt like a performance – like the anonymous girl’s performance.

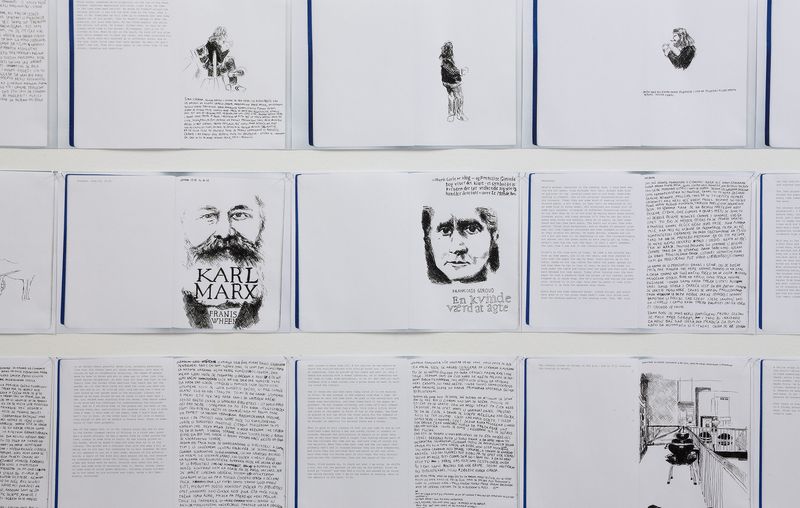

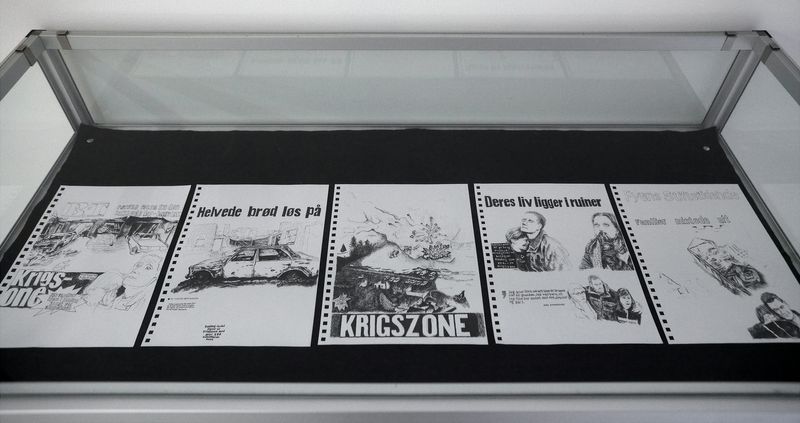

— Put in another way the perceptual method employed by Tolj is apparently a question of making the world perform for us, whether it is through images, an event, through an anonymous person or the artist, personally. The ideal is actually “to make the work happen by itself,” as Ibrahimovic puts it. A good example of this is Ibrahimovic’s piece Seest 03.11.2004 (2008). This work, consisting of photos and delineations of newspaper front pages, is an artistic and personal documentation of the fireworks accident in Seest near Kolding. To Ibrahimovic, the accident held several layers of irony in relation to the issue of identity. Kolding was Ibrahimovic’s Danish hometown and the site of one of Denmark’s first camps for refugees from the Balkans. One of the most significant ironies was that not only did the site of the accident resemble a bombed out Bosnia physically, it was also described and analyzed as a war zone in the media, complete with destroyed homes and devastated families. Whereas these media images caused many Danes to feel like strangers in their own city, the ‘stranger’ Ibrahimovic suddenly experienced his surroundings as familiar and therefore, in a grotesque sense, as assuring.

Obviously dramatic events and spectacular media images also form the basis of Tolj’s work I Love Zagreb from 2008. The work was part of the project Operation City and it was based on a series of dramatic killings in Zagreb the same year. The murders were repercussions of old war conflicts, targeting certain political rulers with surgical precision. Indeed, a crucial victim was the owner of the independent newspaper Nacional, Ivo Pukanic, who was killed in the newspaper’s parking lot. Ironically, the owner of this anti-corruption weekly was involved in complicated mob conflicts himself. The media ran footage from the surveillance camera at the parking lot, showing a man in black with black gloves and a black helmet who drove by on his motorcycle. He parked the MC and walked around without removing his helmet before he disappeared. Later on the motorbike exploded and several individuals were killed. Among the inhabitants of Zagreb the bombing caused widespread fear of motorcyclists moving around in black clothes.

Tolj’s performance was an investigation into the nature of this fear. He walked through the city centre of Zagreb wearing a black motorcycle helmet. Like the contract killer, he had demanded his pay before the job was done. Tolj passed important political and cultural institutions, the HNK (the National Theatre of Croatia) and the Museum of Contemporary Art, past the parliament and the residence of President Mesic and all the way back to his own apartment. Subsequently, the performance was presented in television and newspapers where, noteably, it moved people deeply. Tolj was contacted by a great number of persons who had an urge to tell him that the work was somehow important to them, even if they could not specify any exact reasons.

These reactions from the people of Zagreb indicate that there is a public need, not just an artistic need, for a deeper aesthetical elaboration of the mass-medial and political reality and the feelings, in particular the fear, potentiated by the media. Today, journalism and politics alike are a question of communicating feelings rather than ideological ideas, but this makes neither the media nor politics more humane. Usually, the range of emotions within which the communication unfolds is at once quite limited and highly abstract compared to most people’s full mental reality. It is predominantly a question of intensifying a number of prejudices by distinguishing unequivocally between good and evil, victims and bad guys, innocence and cynicism, feeling safe and feeling insecure. The societal fear, communicated by the media, is an effective guideline for legislation and an operative political tool for the maintenance of power balances. On the other hand, it blurs the more complex emotional reality that people actually live in, but may perceive as alienated, because they do not see it reflected anywhere.

The perceptual method employed by Ibrahimovic and Tolj, each in his way, is among many other things an artistic answer to this condition. In the way the two artists aesthetically play on a number of media generated feelings and notions - and continues them in surprisingly obvious, but deeply poetical images and situations - they both seem to mobilize a more complex and critical view of our emotional reality.